|

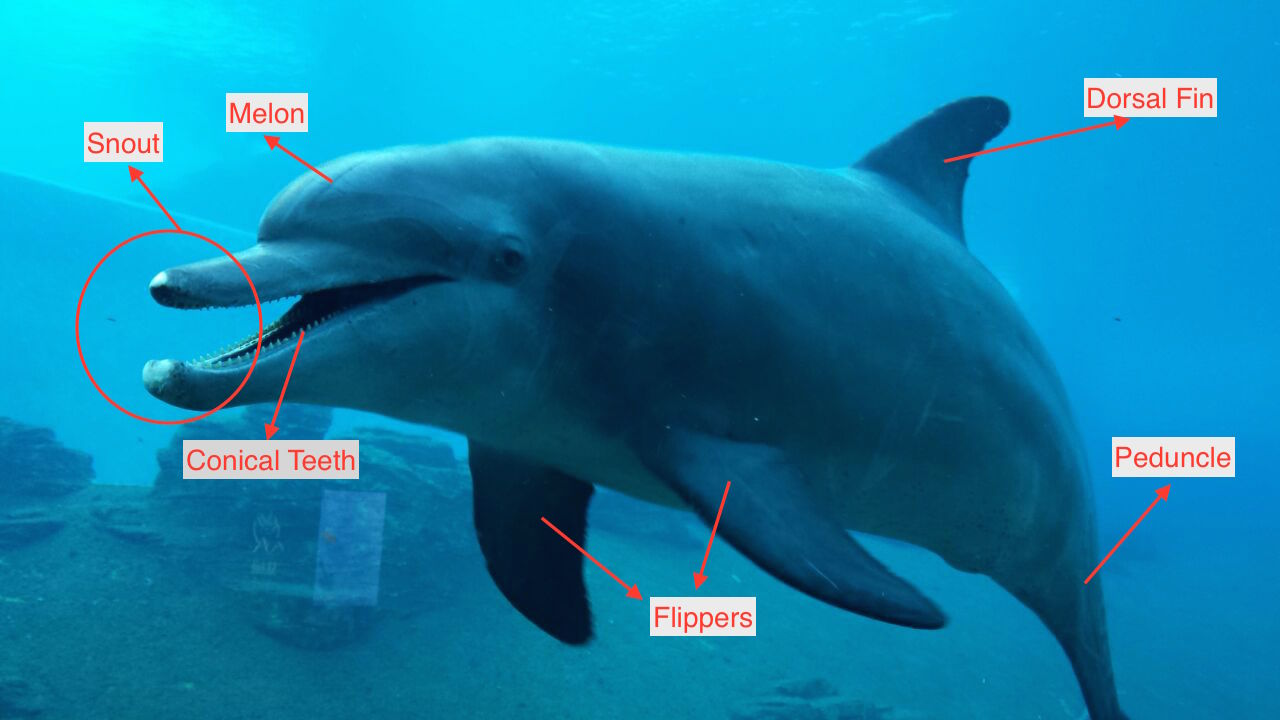

| A curious Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin. Photo reproduction permission granted by Lim Wei Yuen, 2013. |

To know more about...

- the dolphins in captivity controversy

- the physical appearance of the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin

- where they are found in nature

- how they behave in the wild

- how they sleep and breathe concurrently in the water

- their taxonomy

- their conservation challenges around the world

- what you can do to protect these animals

Do not worry if there are terms that are hard to understand. Terms with hyperlinks brings you to the Glossary Section.

Dolphins in Singapore - The controversy

Tursiops aduncus, the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin is a species of dolphin that is found in the seas surrounding Singapore. It is known to many Singaporeans that the housing of Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphins in Resorts World Sentosa (RWS) has created much controversy. Organisations and institutions such as Animal Concerns Research & Education Society: (ACRES) and Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animal (SPCA Singapore) have voiced out strong opinions against the taming and captivity of the dolphins.

The website World's Saddest Dolphins was set up by ACRES in a bid to raise awareness and to appeal for public support against the containment of dolphins within RWS' facilities. SPCA has also called for the release of remaining 24 bottlenose dolphins back into the wild[1], voicing their opposition on the premise that the capturing of wild dolphins for the "purpose of forcing them to adapt to an unnatural lifestyle" should not be accepted.

|

| Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin. Photo reproduction permission granted by Lim Wei Yuen, 2013. |

Looking at this issue from another perspective would allow people to see the possible benefits that arose from the dolphins being held and exhibited to the public in RWS.

This controversy has brought about an increase in awareness and heightened the profile of the dolphins, allowing for people from different walks of life, with different prior knowledge on marine conservation, to understand greater and feel more for the difficulties arising in animal conservation. Without which, aquarium goers might not even be aware that dolphins, cetaceans and other marine animals in the world are facing conservation challenges.

This increase in awareness is especially important, towards triggering movements towards animal conservation and protection.

One should always keep in mind that in the grander scheme of things, sometimes sacrifices are required to be made to achieve a greater goal - stronger conservation awareness and efforts.

"If it is an animal welfare argument, then there is no difference between keeping dolphins and forcing horses to race, or caging singing birds, or keeping fish in aquarium tanks, small or large. If it is a conservation argument, the big picture is that other human activities such as fishing and habitat quality decline do greater damage and kill much more dolphins, and they should be addressed through more effective conservation efforts."-Prof Chou Loke Ming,

director of the Bachelor of Environmental Studies programme at the National University of Singapore [2]

To read more about conservation challenges in other parts of the world, please click here.

1. How do they look like?

Table of Contents

Tursiops aduncus, the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose dolphin has a...

- maximum weight of 230kg

- body length of between 175 and 400cm

- body size shorter and lighter for matured females than matured male[3][4][5]

- countershaded fusiform body for both male and female through having a dark gray back, and a light gray belly scattered with dark gray spots[6]

- lifespan of 19 years for males and 26 years for females on average

- known oldest wild-living dolphin to be a 39 year old male and a 49 year old female[5][6][9]

A simple diagram on the adult Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin's external body parts. Photo is author's own.

Back to top

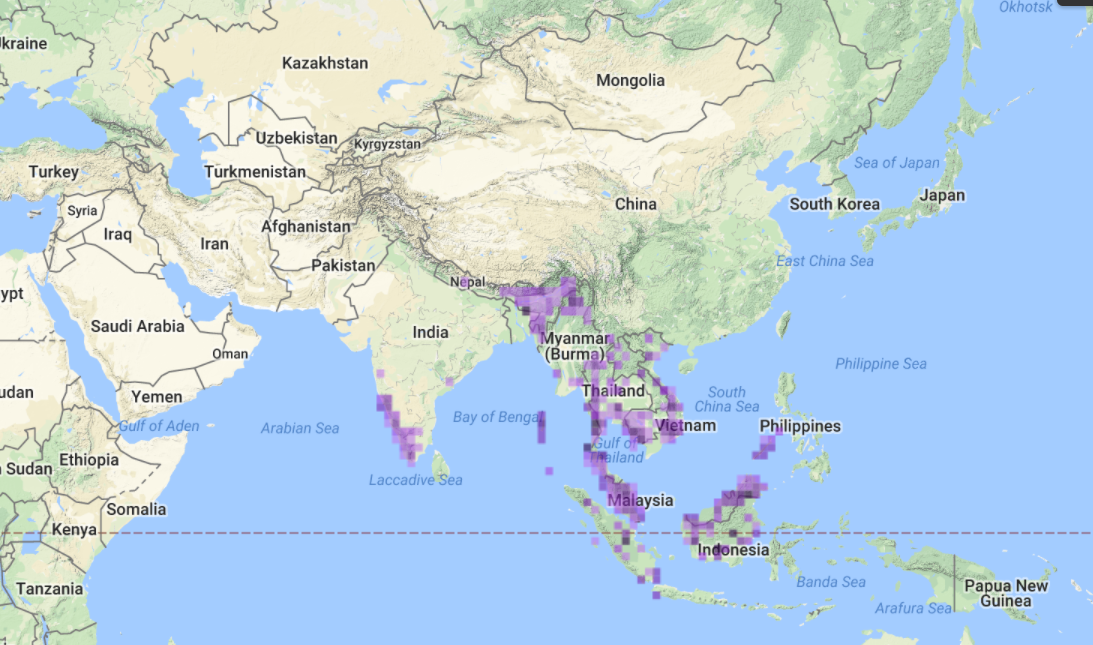

2. Where are they found?

The Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin is only found in the warm coastal waters of the Indo-Pacific and Indian Ocean, including northern Australia[10][11]. Although the Common Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops Truncatus) is also seen in Singapore's waters, the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin is the species of dolphin most predominantly sighted in Singapore waters[12][13].

For a regular update on dolphin sightings in Singapore's waters, you could visit this map created by SWiMMS. It records the time and species of marine mammal sighted.

| Countries in which the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin are sighted[14] |

Native range: Australia; Bahrain; Bangladesh; Brunei Darussalam; Cambodia; China; Comoros; Egypt; Eritrea; India; Indonesia; Iran, Islamic Republic of; Japan; Kenya; Madagascar; Malaysia; Mayotte; Mozambique; Myanmar; Oman; Pakistan; Papua New Guinea; Philippines; Saudi Arabia; Singapore; Solomon Islands; Somalia; South Africa; Sri Lanka; Taiwan, Province of China; Tanzania, United Republic of; Thailand; Timor-Leste; United Arab Emirates; Yemen Possibly extinct: Vietnam |

3. How do they behave?

|

| Social interactions within a pod of dolphins. Author's own image. |

Friendly and sociable interactions

The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins are a group of social animals that forms complex and dynamic relationships with other individuals, which changes frequently[4].These groups usually consist of 2–15 dolphins, and the group members changes accordingly to when predation risk and availability of prey changes[15]. They are also sometimes found in groups with other dolphin species[11].

The Indo-pacific Bottlenose Dolphin face high levels of predation by sharks, especially that from the Tiger shark and Great white sharks in Australia and South Africa. Dolphins are often seen to bear scars of such attacks.

Being hunted by at least ten species of sharks could have resulted in the development of social behaviour that is exhibited by the bottlenose dolphins – travelling in groups results in lower individual vulnerability towards predators[4][16][17].

Back to top

How do they communicate with each other?

The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin’s brain is argued to be so large and complex that it enables each dolphin individual to have highly developed intellect and learning skills. Despite a less developed sense of sight, the dolphins can communicate very effectively via echolocation.Echolocation occurs when the dolphins generate clicks of different ultrasonic frequencies and then interpret returning signals to obtain a mental picture of the environment to detect their prey and predators (see video below). Each individuals also produces a unique whistle that enables other dolphins to identify them individually. Besides echolation, The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin also communicates via tactile signals e.g. rubbing of flippers against the flippers or body of other dolphins[5][8][18][19].

Echolocation of Dolphins from "Ultimate Guide - Secrets of Dolphin Sonar," by Animal Planet Youtube Channel, 13 Sept 2010 [20].

Back to top

What do they feed on?

The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin have a diet consisting mainly of bony fish and to a lesser extent, cephalopods. While these dolphins can feed on a wide range of fish species, they mainly feed on just a few selected species such as Blacktail Snapper (Lutjanus fulvus), Yellowtail Emperor (Lethrinus crocineus) and Slender Conger (Uroconger lepturus)[21].The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins have between 20 to 28 conical and homodont teeth with a diameter of approximately 1cm[5][7][8]. The teeth of the dolphins are not used for chewing or tearing of prey but for capturing and seizing, hence there isn’t a need for molars or for heterodont dentition[22].

|

| (a) Aerial view of Tursiops aduncus skull |

|

| (b) Close up on lower jaw of Tursiops aduncus |

|

| Close up on Tursiops Aduncus jaws(a), (b), (c), showing homodont dentition of the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin, photo reproduction permission granted by Marcus Chew, 2014. |

These social creatures have a cooperative hunting and foraging behaviour characterized by several shallow dives per minute. The dolphins’ hunting methods in shallow waters includes chasing small fish up onto the shore and trapping them within a circle of mud in the water (see video below) and also “knocking” the fish into the sand with their tail flukes. Hunting occurs most often in the morning and afternoon[5][6][19][21].

"Dolphins trick fish with mud "nets" - One Life" by BBC Earth Youtube Channel, 8 Feb 2013.[49]

Back to top

How do they reproduce?

Reproductive Maturity |

| Freckling of ventral side of Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin. Image by © M. Watson. Picture taken from Arkive.com. Photo reproduction permission granted under Terms and Conditions of Photo use. Source: http://www.arkive.org/indian-ocean-bottlenose-dolphin/tursiops-aduncus/image-G36915.html |

Female Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphins reaches reproductive maturity between 7 and 12 years of age whereas that of males is between 9 and 13 years old.

Reproductive maturity is shown to the males through visible development of freckles on the ventral side of the body. The gestation period is approximately 12 months.

Strategies for reproductive Success

It is interesting to know that female reproductive success is higher in shallow waters as it is easier to detect predators and reduces overall predation by sharks[4][5][6][23].

The Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin exhibits a rare trait that is found by few mammal species - the cooperation of males to allow for easier mating with females. Males form alliances with up to three other potentially unrelated males, and they herd females for mating (see video below). This action is sometimes called “mate guarding.” Both male and female Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphins tend to mate with more than one partner[17][24].

Mate guarding in "World's Weirdest - Promiscuous Dolphins" by NatGeoWild Youtube Channel, 11 Apr 2012.[50]

What do we know about their young?

The Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin at birth has a length of between 0.8 and 1.1m, weighing between 9 and 21 kg. The highest rates of birth occur between October and December. The lactation period last for approximately 18 months in captivity and 32 months in the wild[3][4][5][6][19].

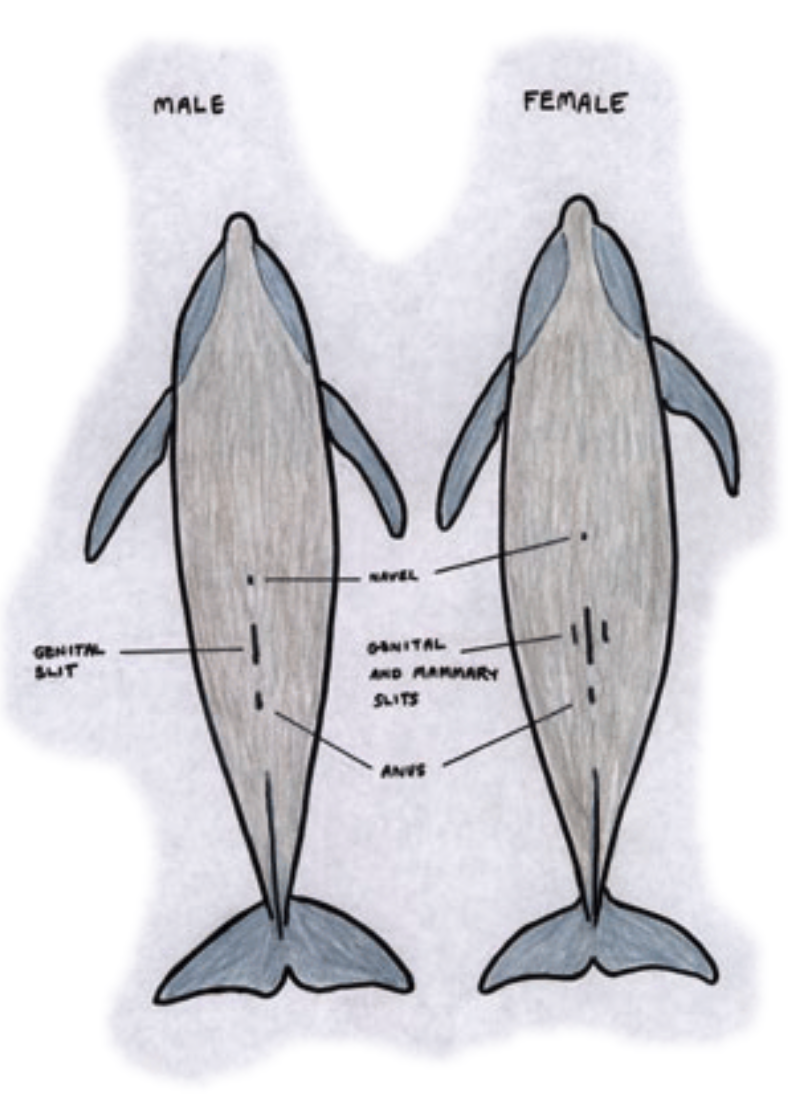

|

| Artist impression of urogenital slits of both male and female bottlenose dolphins. Image source: Dolphin Web. Source: https://www.tangalooma.com/dolphinweb/schoolprojects/theme4.asp |

| Comparison between external reproductive structure[25] |

|

|---|---|

| Male |

Female |

|

|

Back to top

How do they rest in the ocean?

As the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphins are mammals, it is required for them to surface to breathe in oxygen from the air even when they sleep. It was therefore hypothesized by Lilly[26] that by resting only half their brain at any one time and keeping one eye open, the dolphins could still consciously surface to breathe even during sleep[32]. The singular open eye helps to scan the environment for predators. It was also postuated by Goley[27] that the opening of one eye could also be to maintain visual contact with other pod members. Electrophysiological studies[28][29][30] have shown that dolphins indeed have one eye open during their sleep. Further studies have affirmed the sentinel duty of the open eye of the dolphin[31]. Back to top4. Taxonomy

Taxonavigation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class: Mammalia |

|||||

| Order: Cetacea |

|||||

| Suborder: Odontoceti |

|||||

| Family: Delphinidae |

|||||

| Genus: Tursiops |

|||||

| Species: Aduncus |

Synonyms[33] |

| Delphinus abusalam Ruppell 1842, Delphinus hamatus Wiegmann 1841, Delphinus perniger Blyth 1848, Sotalia gadumu Owen 1866, Sotalia perniger Trouessart 1898, Tursio abusalam Ruppell 1842, Tursiops abusalam Ruppell 1842, Tursiops catalania Gray 1862, Tursiops fergusoni Lydekker 1903, Tursiops nuuanu Andrews 1911 |

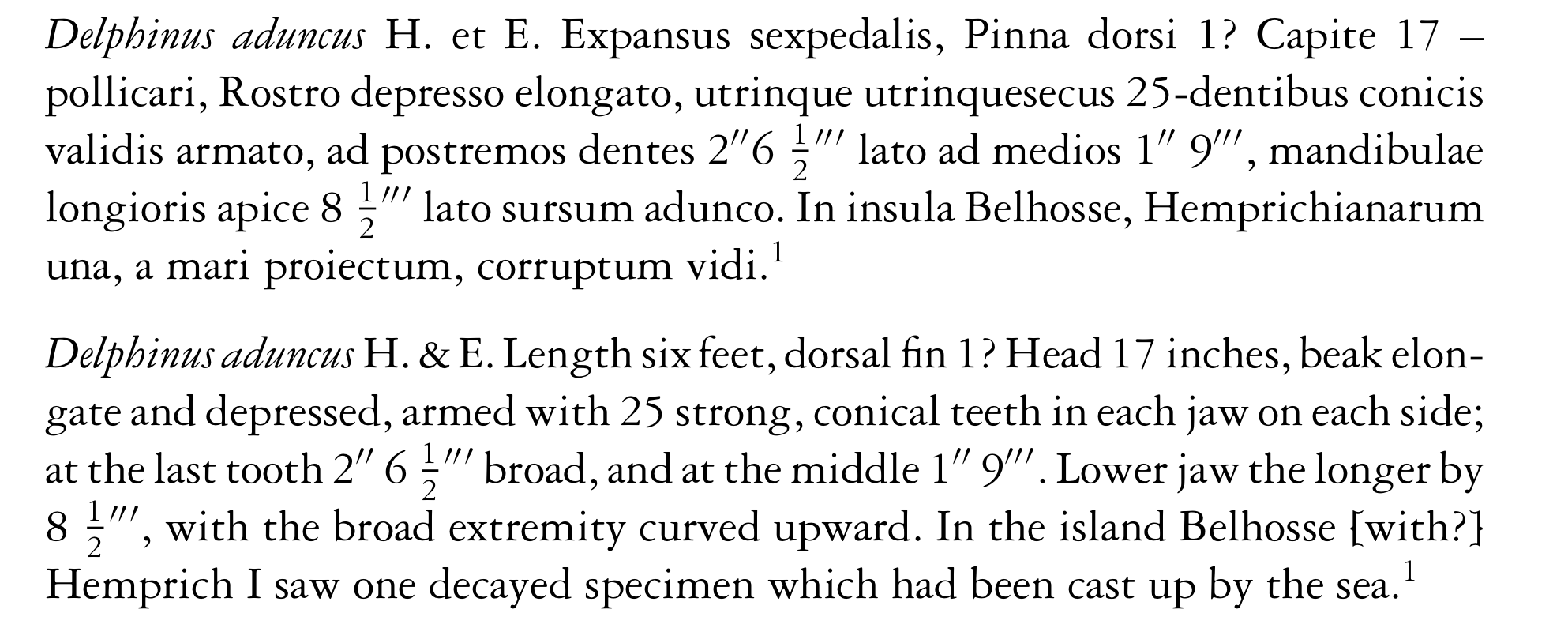

Original Specimen

This species was originally designated the scientific name Delphinus aduncus[34], of which no diagnostic details to distinguish it from the sympatric Tursiops truncatus was given. It was initially thought that the description was based on describing a stranded animal and thus no holotype specimen was kept and designated by Ehrenburg[35]. However, the Tursiops skull was subsequently discovered deposited in the Berlin Museum, mistakenly described as Delphinus rostratus. The skull was then later reconsidered and identified as the missing holotype specimen of Tursiops aduncus collected from the Indian Ocean due to its antiquity in 1978. The holotype skull (ZMB66400) is currently stored in the Zoologisches Museum Berlin (ZMB), Humboldt Universität zu Berlin Museum für Naturkunde[36]. |

| Original description (as Delphinus aduncus) by Hemprich and Ehrenberg (1832).English translation extracted from True [37]. |

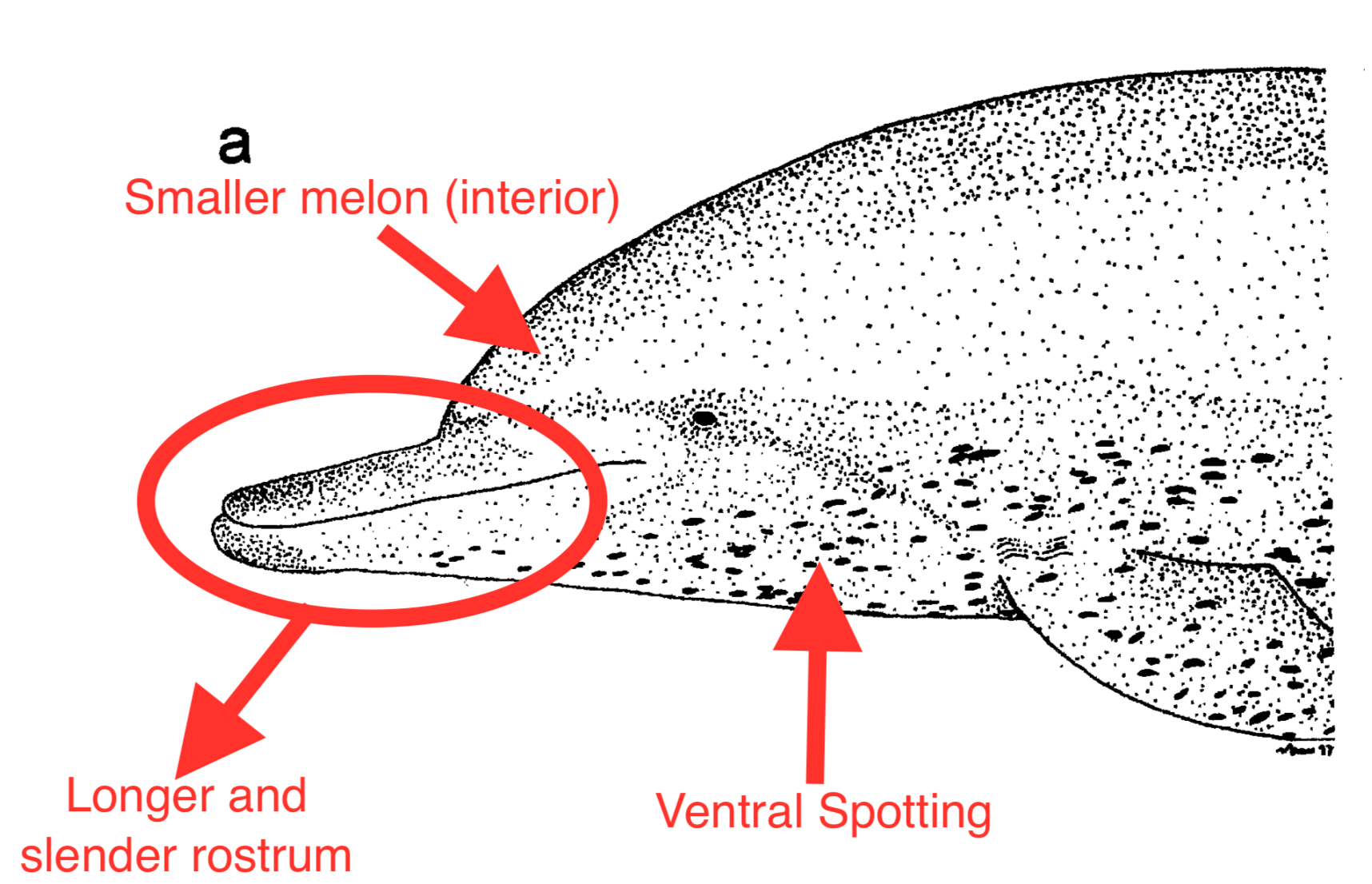

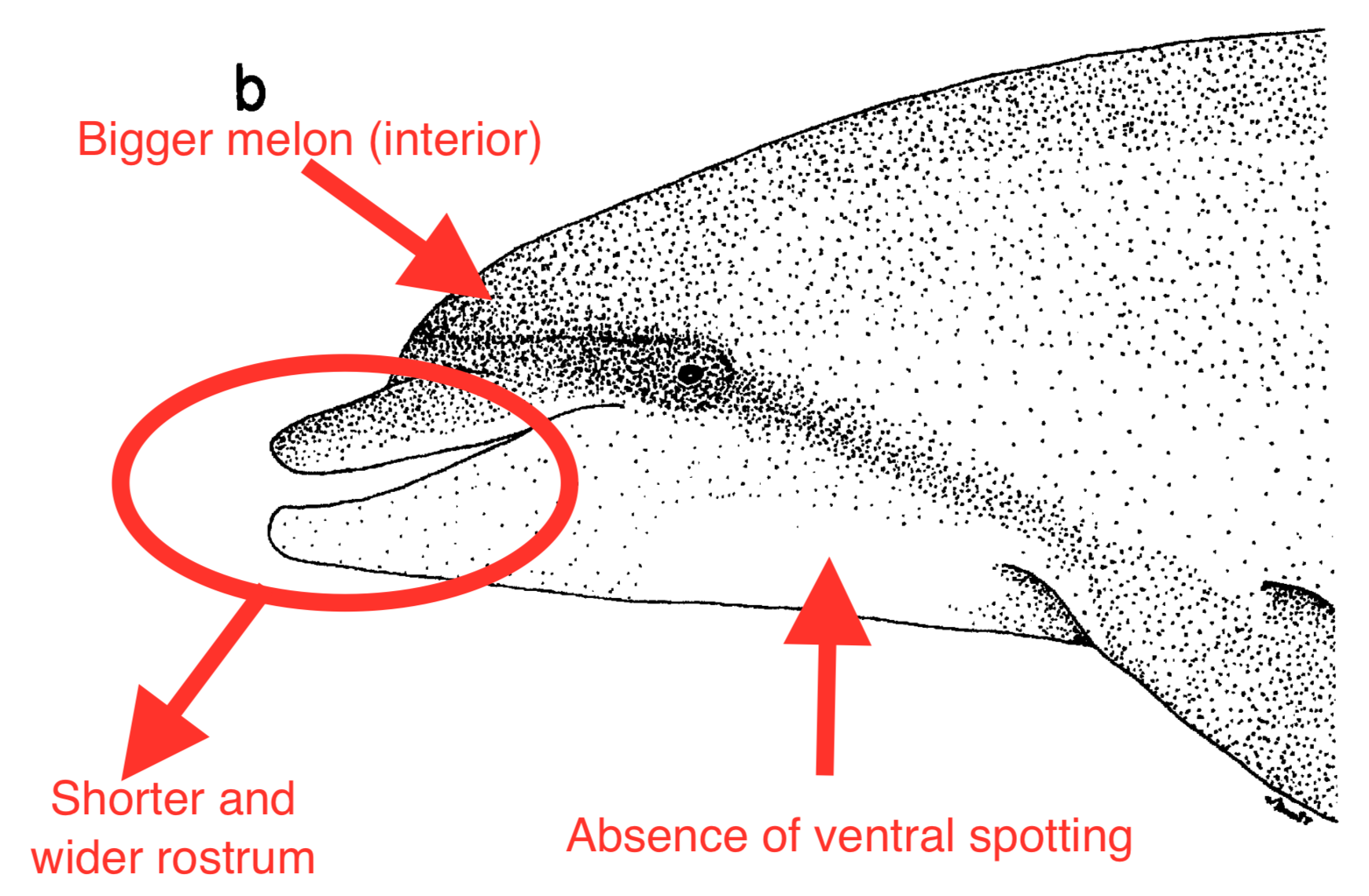

How do you tell between the two species found in Singapore's waters?

Both Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops Aduncus) and Common Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops Truncatus) are found in Singapore waters. In Southeast Asia, both species are sympatric and are often even found in mixed schools[11]. In fact, in Singapore, other dolphins and marine mammals has been sighted, more about them can be discovered here.

| Comparison of several physical differences between Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin and Common Bottlenose Dolphin[3][6][7][38] |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Species |

Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops aduncus) |

Common Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) |

||||

| Freckling |

|

|

||||

| Body Size |

|

|

||||

| Head and Melon |

|

|

||||

| Rostrum |

|

|

||||

| Flippers |

|

|

||||

| Dorsal Fin |

|

|

||||

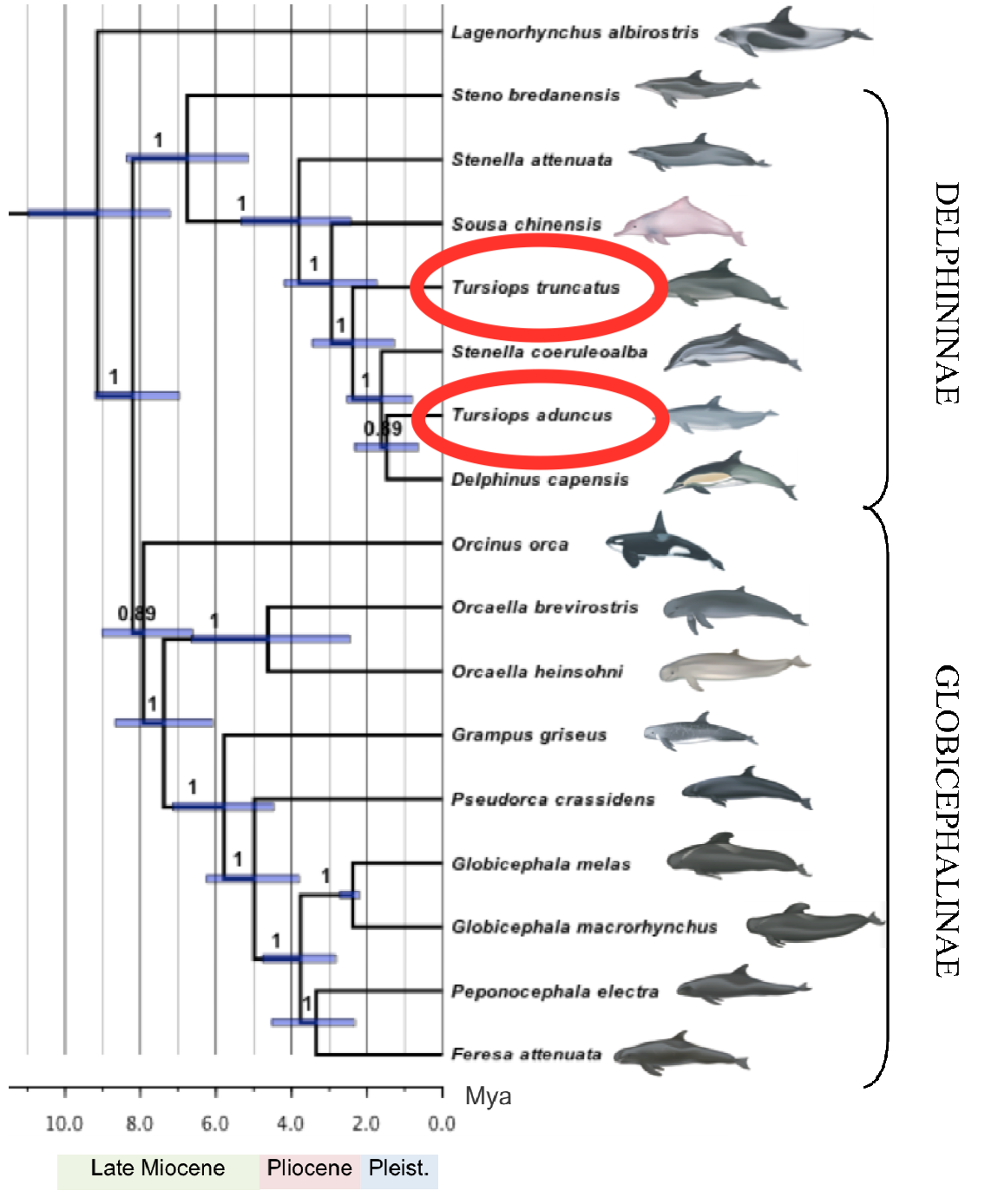

Taxonomic Dispute

The taxonomic status of the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops aduncus) was uncertain until 2000 when studies demonstrated that Tursiops aduncus and Tursiops truncatus was reproductively isolated. South African bottlenose dolphins were previously named as either Tursiops aduncus or Tursiops truncatus on the basis of differences in size and morphological characters[39].Lack of hybridization evidences highlights the reproductive isolation between Tursiops aduncus and Tursiops truncatus. There is a lack of reported hybridization between the two forms of Tursiops despite the great prevalence of hybridization reports between species of dolphins and other cetaceans[40].

In captivity, hybrids with Risso's dolphin Grampus griseus, short-finned pilot whale Globicephala macrorhynchus, rough-toothed dolphin Steno bredanensis and the false killer whale Pseudorca crassidens were produced[41]. In the wild, three hybrids of Tursiops truncatus and G. griseus were reported by Fraser[42]. It is therefore interesting to note that only a single hybrid was reported between Tursiops aduncus and Tursiops truncatus. Institutions such as Ocean Park, Hong Kong and Ocean world Taipei, Taiwan has kept both species of Tursiops within the same containing area for many years without occurrences of hybridization[41]. The maintenance of reproductive isolation between the two sympatric populations of Tursiops satisfies the criterion of the Biological Species Concept[43] to be two distinct species.

Recent analyses carried out on the osteology and the external morphology of sympatric populations Tursiops aduncus and Tursiops truncatus in Chinese waters showed the two Tursiops to be separate species[40].

A study analyzing mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) control region sequences of both species showed a clear division of two lineages[40][45], supporting that Tursiops aduncus and Tursiops truncatus are separate species. In fact, mtDNA control region sequences of Tursiops truncatus from the China sea are more closely related to that of Tursiops truncatus from the Atlantic Ocean than that of sympatric T. aduncus[44].

In another study conducted that generated the mitogenome sequences, with at least 1 complete genome sequenced for each stated species in the below figure showed a bootstrap value of 1 on the Bayesian phylogenetic tree, indicating that Tursiops aduncus and Tursiops truncatus are clearly separate species[51].

|

| Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction of selected taxa within Delphinidae using 21 partitioned mitogenome sequences. Adapted from Vilstrup et al., 2011[51] |

Back to top

5. Conservation challenges

Around the world

What are the human impacts on the dolphins?

Dolphins are often hunted and captured for food[4][16] despite ban of direct harvesting of the dolphins for human consumption in 1990. They are also often incidentally being part of by catches, getting caught particularly in purse seine and gillnet fisheries[17]. As such, thousands of dolphins have been taken each year in Taiwan, Australia, South Africa.

Live captures of Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphins also occur due to their global popularity particularly in Taiwan, Japan, Indonesia [46]and this has resulted in a rapidly expanding eco-tourism industry.

Increased contact with humans (performances, provisional feeding of animals) have also brought about changes in the behaviour and distribution of the dolphins[47].

Furthermore, the preference of the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphins for shallow coastal waters brings the dolphins closer to coastal pollution brought about by surface runoff and sedimentation, reduced prey populations as a result of overfishing, bioaccumulation of harmful chemicals along the marine food chain, disturbance by commercial and recreational vessel traffic and also increased noise pollution that affects their echolocation and thus hunting abilities[48].

What can you do to protect these animals?

- Avoid consuming meats of marine mammals such as whales and dolphins

- Discover how waste is treated and released into the wild in your country

- Avoid patronising establishments with uncertified ways of taking care of their animals within captivity

- Be more aware of laws that governs the trade of endangered animals: CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora)

- Learn more about the conservation status of animals around the world from IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature)

Back to top

6. Glossary

| Biological Species Concept |

A concept that defines species as groups of organisms that can interbreed in nature, successfully having several reproductive generations. |

| Cephalopod |

A group of marine organisms with a prominent head and a set of arms or tentacles. Commonly know cephalopods are squids, octopuses, nautiluses etc. |

| Cetacean |

Consists of a group of marine mammals containing whales, porpoises and dolphins. |

| Countershade |

A form of camouflage whereby the colouration pattern of the animal is darker at the top and lighter at the underside of the body. Commonly seen in marine animals such as sharks, dolphins, rays etc. |

| Electrophysiological |

The study of electrical properties of cells and tissues within the body |

| Foraging |

Searching for food sources in the wild |

| Fusiform |

A common body shape, characterized by the tapering at both the head and the tail, for many aquatic animals. |

| Gestation |

The time period where the foetus is held within the mother's body between conception and birth |

| Heterodont dentition |

Having different forms of teeth e.g. molar, canines, incisors, premolars |

| Holotype/type specimen |

The original specimen in which a description of a new species is made from |

| Homodont dentition |

All teeth having the same shape |

| Hybridisation |

The process where two different species or breeds produce an offspring. The resulting offspring is known as a hybrid. |

| Lactation |

The secretion of milk from the mammary glands of a mother to feed her young. |

| Lifespan |

Expected length of life |

| Lineages |

An evolutionary understanding and portrayal of a line of descent, with each species as a result of speciation from the direct ancestral species |

| Mammal |

A group of warm blooded animals distinguished by the presence of hair, mammary glands and breathing through lungs. |

| Mitogenome |

The DNA located in the mitochondria. |

| Morphological |

Morphology is the study of the form and structure of organisms, both internal and external. |

| Native range |

The natural regions and area that the species is found in, without human intervention. |

| Osteology |

The scientific study of bones |

| Reproductive Isolation |

The inability for different species to breed and produce offsprings that are virile. |

| Scientific name |

A formal naming system of living organisms that has two parts. Both words are in Latin. The first part refers to the genus and second part the species e.g. Homo sapiens Genus: Homo. Species: sapiens |

| Sympatric |

Two species are considered sympatric if they exist within the same geographical range and thus encounters each other. |

| Synonym |

A scientific name that has been previously used to name a specific taxon. |

| Tactile |

The sense of touch |

| Taxon (Singular) Taxa (Plural) |

A grouping of organisms, by taxonomists, to form a unit. Commonly known taxa are Kingdom, Phylum, Species etc. |

| Ultrasonic frequency |

A frequency of sound that exceeds the upper limit of the human audible range. |

| Ventral |

The underside of the body. |

Back to top

7. Literature and References

[1] "SPCA Calls for release of Resorts World Sentosa dolphins after fourth death", by The Straits Times. URL: http://www.spca.org.sg/pdf/RWSDolphin2014/Asiareport06042014.pdf (accessed on 20 Nov 2014)

[2] "Conservationists find Marine Life Park partnership with Conservation International puzzling", by Jeanette Tan. URL: http://www.saddestdolphins.com/latestnews/2014/Jan%202014%20Conservationists%20find%20Marine%20Life%20Park%20partnership%20with%20Conservation%20International%20puzzling.pdf (accessed on 20 Nov 2014)

[3] Kogi, K., T. Hishii, A. Imamura, T. Iwatani & K. Dudzinski, 2004. Demographic parameters of indo-pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) around Mikura Island, Japan. Marine Mammal Science, 20(3): 510–526.

[4] Mann, J., R. C. Connor, L. M. Barre & M. R. Heithaus, 2000. Female reproductive success in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.): life history, habitat, provisioning, and group-size effects. Behavioral Ecology, 11(2): 210–219.

[5] Nowak, R., 2003. Walker's Marine Mammals of the World. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

[6] Shirihai, H. & B. Jarrett, 2006. Whales, Dolphins, and Other Marine Mammals of the World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[7] Kurihara, N. & S. Oda, 2007. Cranial variation in bottlenose dolphins Tursiops spp. from the Indian and western Pacific Oceans: additional evidence for two species. Acta Theriologica, 52(4): 403–418.

[8] Martin, R., R. Pine & A. DeBlase, 2001. A Manual of Mammalogy with Keys to Families of the World. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

[9] Klinowska, M. & J. Cook, 1991. Dolphins, Porpoises and Whales of the World: The IUCN Red Data Book. Cambridge, England: IUCN.

[10] Rice, D. W., 1998. Marine mammals of the world: Systematics and distribution. Special Publication No. 4. The Society for Marine Mammalogy, Lawrence, KS.

[11] Wang, J. Y., L. S. Chou, & B. N. White, 2000. Differences in the external morphology of two sympatric species of bottlenose dolphins (genus Tursiops) in the waters of China. Journal of Mammalogy, 81(4): 1157–1165.

[12] “Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops aduncus)” by Marine Mammal Research Laboratory. Singapore Wild Marine Mammal Survey, 28 July 2011. URL: http://www.tmsi.nus.edu.sg/mmrl/tursiops.htm (accessed 7th Sept 2014)

[13] Wells, R. S. & M. D. Scott, 2002. Bottlenose dolphins. In: Perrin W.F., B. Würsig, & J.G.M. Thewissen, eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. San Diego: Academic Press.

[14] "Tursiops aduncus", by The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. URL: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/41714/0 (accessed on 20 Nov 2014)

[15] Mann, J. & H. Barnett, 1999. Lethal tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) attack on bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops sp.) calf: Defense and reactions by the mother. Marine Mammal Science, 15(2): 568–575.

[16] Heithaus, M.R., 2001. Predator-prey and competitive interactions between sharks (order Selachii) and dolphins (soborder Odontoceti): a review. Journal of Zoology, 253(1): 53–68.

[17] Reynolds, J., R. Wells & S. Eide, 2000. The Bottlenose Dolphin: Biology and Conservation. Florida: University Press of Florida.

[18] Sakai, M., T. Hishii, S. Takeda & S. Kohshima, 2006. Flipper rubbing behaviors in wild bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus). Marine Mammal Science, 22(4): 966–978.

[19] Vaughan, T., J. Ryan & N. Czaplewski, 2011. Mammalogy. Boston, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

[20] “Ultimate Guide - Secrets of Dolphin Sonar," by Animal Planet Youtube Channel, 13 Sept 2010. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZoNDW0zSRNo (accessed on 25 Oct 2014)

[21] Amir, O. A., P. Berggren, G. M. S. Ndaro & N. S. Jiddawi, 2005. Feeding ecology of the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops aduncus) incidentally caught in the gillnets fisheries off Zanzibar, Tanzania. Estuarine. Coastal and Shelf Science, 63(3): 429–437.

[22] Rauch, A., 2013. Dolphin. London: Reaktion books.

[23] Krzyszczyk, E. & J. Mann, 2012. Why become speckled? Ontogeny and function of speckling in Shark Bay bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops spp.). Marine Mammal Science, 28(2): 295–307.

[24] Möller, L., L. Beheregaray, R. Harcourt & M. Krützen, 2001. Alliance membership and kinship in wild male bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) of southeastern Australia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Biological Sciences, 268: 1941–1947.

[25]"Sex and reproduction in the Bottlenose Dolphin" by DolphinWeb. URL: https://www.tangalooma.com/dolphinweb/schoolprojects/theme4.asp (accessed on 20 Nov 2014)

[26] Lilly, J. C., 1964. Animals in aquatic environments: adaptations of mammals to the ocean. In: Dill, D.B. (Ed.), Handbook of Physiology—Environment. American Physiology Society, Washington, DC, pp. 741–747.

[27] Goley, P. D., 1999. Behavioral aspects of sleep in pacific white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens, Gill 1865). Marine Mammal Science, 15: 1054–1064.

[28] Mukhametov, L. M. & A. Y. Supin, 1975. An EEG study of different behavioural states in free moving dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). Zhurnal vyssh. Nerv. Deyat. I. P. Pavlovas, 25: 396–401

[29] Mukhametov, L. M., A. Y. Supin & I. G. Polyakova, 1977. Interhemispheric asymmetry of the electroencephalographic sleep pattern in dolphins. Brain Research, 134(3): 581–584.

[30] Serafetinides, E. A., J. T. Shurley, & R. E. Brooks, 1972. Electroencephalogram of the pilot whale, Globicephala scammoni, in wakefulness and sleep: lateralization aspects. Int. J. Psychobiol, 2: 129–135.

[31] Mukhametov, L. M., O. I. Lyamin, 1997. The Black Sea bottlenose dolphin: the conditions of rest and activity. In: Sokolov, V.E., Romanenko, E.V. (Eds.), The Black Sea Bottlenose Dolphin. Nauka, Moscow, pp. 650–668.

[32] Lyamin, O. I., P. R. Manger, S. H. Ridgway, L. M. Mukhametov &, J. M. Siegel, 2008. Cetacean sleep: An unusual form of mammalian sleep. Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews, 32: 1451–1484.

[33] "Tursiops aduncus Ehrenberg 1832 (dolphin)," by Paleobiology Database. URL: http://paleobiodb.org/cgi-bin/bridge.pl?a=basicTaxonInfo&taxon_no=69767 (accessed on 20 Oct 2014)

[34] Hemprich, C.G., & W. F. Ehrenberg, 1832. Symbolae Physicae Mammalia, 2: footnote on last page of unpaginated fascicle headed Herpestes leucurus H. et E. Berlin, Germany.

[35] Hershkovitz, P., 1966. Catalog of living whales. United States National Museum Bulletin 246:1–259.

[36] Perrin, W. F., K. M. Robertson, P. J. H. van Bree & J. G. Mead, 2007. Cranial Description and Genetic Identity of the Holotype Specimen of Tursiops aduncus (Ehrenberg, 1832). Marine Mammal Science, 23(2): 343–357.

[37] True, F. W., 1914. On Tursiops catalania and other existing species of bottlenose porpoises of that genus. Annals of the Durban Museum 1(Part 2):10–24.

[38] Natoli, A., V. M. Peddemorsanda, R. Hoelzel, 2004. Population structure and speciation in the genus Tursiops based on microsatellites and mitochondrial DNA analyses. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 17: 363–375.

[39] Ross, G. J. B., 1977. The taxonomy of bottlenosed dolphins Tursiops in South African waters, with notes on their biology. Annals of the Cape Provincial Museums. Natural History, 11(9): 135–194.

[40] Wang, J. Y., L. S. Chou, & B. N. White, 2000. Osteological differences between two sympatric forms of bottlenose dolphins (genus Tursiops) in Chinese waters. The Zoological Society of London, 252: 147–162.

[41] Sylvestre, J. & S. Tasaka, 1985. On the intergeneric hybrids in cetaceans. Aquatic Mammals, 11: 101–108.

[42] Fraser, F. C., 1940. Three anomalous dolphins from Blacksod Bay, Ireland. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 45: 413–455.

[43] Mayr, E., 1942. Systematics and the origin of species. New York: Columbia University Press.

[44] Wang, J. Y., L. S. Chou, & B. N. White, 1999. Mitochondrial DNA analysis of sympatric morphotypes of bottlenose dolphins (genus: Tursiops) in Chinese waters. Molecular Ecology, 8: 1603–1612.

[45] LeDuc, R. G., W. F. Perrin & A. E. Dizon, 1999. Phylogenetic relationships among the delphinid cetaceans based on full cytochrome b sequences. Marine Mammal Science, 15: 619–648.

[46] Reeves, R. R., Smith, B. D., Crespo, E. A. & Notarbartolo di Sciara, G, 2003. Dolphins, Whales and Porpoises. IUCN. URL: https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/2003-009.pdf (accessed 19 Oct 2014)

[47] Constantine, R., D. H. Brunton & T. Dennis, 2004. Dolphin-watching tour boats change bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) behaviour. Biological Conservation, 117(3): 299–307.

[48] Bejder, L., A. Samuels, H. Whitehead, N. Gales, J. Mann, R. Connor, M. Heithaus, J. Watson-Capps, C. Flaherty & M. Krutzen, 2006. Decline in relative abundance of bottlenose dolphins exposed to long-term disturbance. Conservation Biology, 20(6): 1791–1798.

[49] "Dolphins trick fish with mud "nets" - One Life - BBC", by BBC Earth Youtube Channel, 8 Feb 2013. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bzfqPQm-ThU (accessed 20 Nov 2014)

[50] "World's Weirdest - Promiscuous Dolphins", by National Geographic Wild Youtube Channel, 11 Apri 2012. URL:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mdoFKNbqKE (accessed 20 No 2014)

[51] Vilstrup, J. T., S. Y. W. Ho, A. D. Foote, P. A. Morin, D. Kreb, M, Krützen, G. J. Parra, K. M. Robertson, R. de Stephanis, P. Verborgh, E. Willerslev, L. Orlando & M. T. P. Gilbert, 2011. Mitogenome phylogenetic analyses of the Delphinidae with an emphasis on the Globicephalinae. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 11(65): 1–10.